Abstract

Free access to knowledge is a central module within the context of Science 2.0. Rapid development within the area of Open Access underlines this fact and is a pathfinder for Science 2.0, especially since the October 2003 enactment of the “Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities”.

Open Access saves lives. Peter Murray-Rust

Introduction

The past years have shown that Open Access is of high relevance for all scientific areas but it is important to see that the implementation is subject-tailored. In all journal based sciences two both well-established and complementary ways used are “OA gold” and “OA green”. These two ways offer various advantages that enhance scientific communication’s processes by allowing free access to information for everybody at any time.

Furthermore, it is necessary to break new ground in order to expand, optimize, and ensure free worldwide access to knowledge in the long run. All involved players need to re-define their role and position in the process. This challenge will lead to new, seminal solutions for the sciences.

Definition of Open Access

Open Access implies free access to scientific knowledge for everybody. In the “Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities“, the term scientific knowledge is defined as “ original scientific research results, raw data and metadata, source materials, digital representations of pictorial and graphical materials and scholarly multimedia material“. Most scientific knowledge is gained in a publicly funded context; basically it is paid for by the taxpayer. In many fields, journals are the main channel of scholarly communication, therefore Open Access has especially developed in this sector. At the moment, most scientific journal articles are only accessible to scientists who are working in an institution with a library that has licensed the content. According to the “Berlin Declaration”, not only a “free, irrevocable, worldwide, right of access” should be granted, but also a “license to copy, use, distribute, transmit and display the work publicly and to make and distribute derivative works, in any digital medium for any responsible purpose (…) as well as the right to make small numbers of printed copies for their personal“.

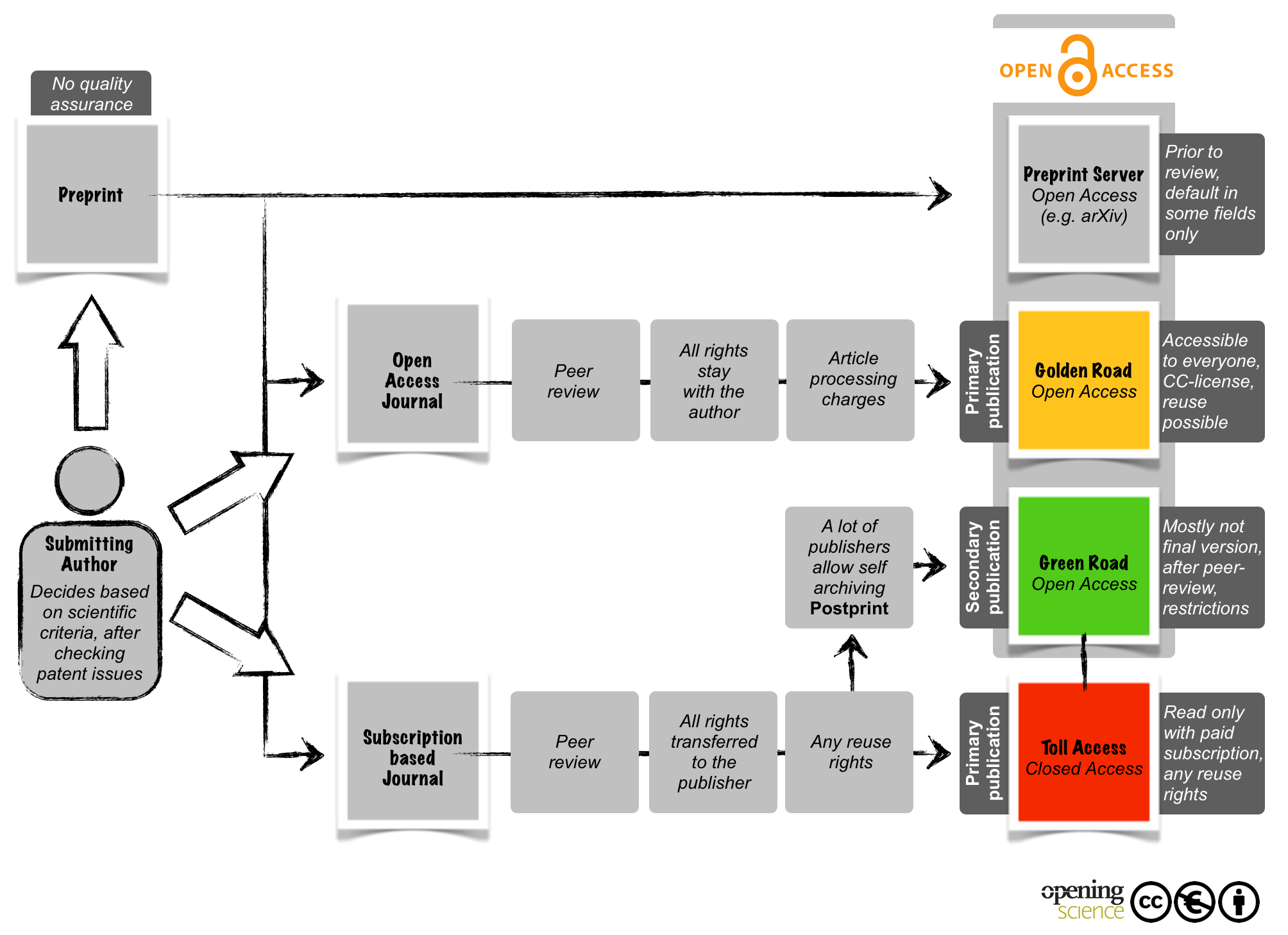

Authors have several possibilities in publishing their research results. Open Access maximizes the visibility and outreach of the authors’ publications and the results of public funding (Figure 1).

State of the Art

Open Access today is an accepted and applauded scientific publication strategy. In summer 2012, a number of statements impressively showed the state of the art as it was seen by national and international actors of science politics and science management.

The European Commission published its vision on how to improve access to scientific information. Two citations from this occasion’s press release and the related communication represent this perspective:

“As a first step, the Commission will make open access to scientific publications a general principle of Horizon 2020, the EU’s Research & Innovation funding program for 2014-2020. As of 2014, all articles produced with funding from Horizon 2020 will have to be accessible: articles will either immediately be made accessible online by the publisher (‘Gold’ open access)—up-front publication costs can be eligible for reimbursement by the European Commission; or researchers will make their articles available through an open access repository no later than six months (12 months for articles in the fields of social sciences and humanities) after publication (‘Green’ open access)” (see Press Releases RAPID).

“The European Commission emphasises open access as a key tool to bring together people and ideas in a way that catalyses science and innovation. To ensure economic growth and to address the societal challenges of the 21st century, it is essential to optimize the circulation and transfer of scientific knowledge among key stakeholders in European research—universities, funding bodies, libraries, innovative enterprises, governments and policy-makers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and society at large.”1

Hence, we can expect that results from the European research program Horizon 2020 should be fully open access. Already in the current program, published results from the fields of energy, environment, health, information and communication technologies, and research infrastructures are expected to be open access, according to an Open Access Pilot for these subjects.

“…beneficiaries shall deposit an electronic copy of the published version or the final manuscript accepted for publication of a scientific publication relating to foreground published before or after the final report in an institutional or subject-based repository at the moment of publication. Beneficiaries are required to make their best efforts to ensure that this electronic copy becomes freely and electronically available to anyone through this repository:

- immediately if the scientific publication is published “open access”, i.e. if an electronic version is also available free of charge via the publisher, or

- within [X] months of publication …”

In June 2012, the Royal Society published a report named “Science as an open enterprise” which aimed for research data to be an integral part of every researcher’s scientific record, stressing the close connection of open publication and open accessible research data (see Chapter 14, Pampel & Dallmeier-Tiessen: Open Research Data). “Open inquiry is at the heart of scientific enterprise … We are now on the brink of an achievable aim: for all science literature to be online, for all of the data to be online and for the two to be interoperable” (Boulton & et al. 2012).

In several countries, initiatives are afoot to build a legal foundation to help broadening the road to a world of openly accessible scientific results. Just to name a few:

- In Great Britain, the minister for universities and science, David Willetts, strongly supports a shift to free access to academic research. The British government actually plans to open access to all publicly funded research by 2014 (cf. Willetts 2012).

- In the United States, an initiative called Federal Research Public Access Act (FRPAA) is on the way, requiring “free online public access“.

- In Germany, the Alliance of German Science Organizations is a strong supporter of an initiative for a change in German Copyright law which is supposed to secure a basic right for authors to publish their findings in accordance to the idea of providing scientists free access to information (see Priority Initiative “Digital Information”).

Since the Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI 2002) was inaugurated, a number of declarations of different bodies have paved the way. Indeed, the list of signatories of the “Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities” read like a gazetteer of scientific institutions and organizations worldwide.

Due to a series of follow-up conferences, the number of supporters of the Berlin Declaration is still growing. Moreover, some US universities took the opportunity to join in when the conference took place Washington DC in December 2011.

Already at an early stage, funding bodies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) stepped in and created rules for the openness of their funded research. National funders like DFG in Germany, SURF in the Netherlands, JISC in GB, and others not only asked for open results of their funded projects, but also featured change by funding calls for projects to do research on Open Access and to develop appropriate infrastructure.

One of the boosters for this rapid development of support for Open Access was, of course, the “journal crisis”. Since the early 1990’s, we have seen a dramatic change in the scientific publication landscape, especially for journals which had basically not changed since they were established. One other aspect was a long series of mergers of publication houses, leaving us with four big players controlling about 60 to 70 percent of journal titles worldwide. Here, stock exchange perspectives and risk money from private equity funds are playing an important and shaping role. Another change factor lies in the possibilities of the Internet. Already in the early days of the Internet, ArXiv was established. ArXiv already displayed the benefits of Open Access within a small, and for a long time closely cooperating community, Particle Physics. Publishers used their monopoly and increased journal prices over the years at very high rates; at least 10 percent per year was the standard for years. Although these rates have lowered a little in the last few years (five to six percent per year), since the late nineties, most libraries have had problems keeping up with the subscriptions to journals which they should hold for the benefit of researchers. As a result, they have cancelled journal subscriptions. Even today, big and famous libraries cancel journal subscriptions, like the Faculty Advisory Council suggested for Harvard in 2012.2 In former days, moderate prices guaranteed that, at least in the Western world, the possibility somehow of providing access to scientific output. In these times of a continuing “journal crisis”, fewer and fewer scientists get access to journals, especially in science, technology, and medicine, and therewith to scientific knowledge, because not all institutions can afford the ever rising subscription fees. This day to day experience of many scientists enormously helped to build the vision of science based on openly accessible publications.

In economic theory, Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom extended her concept of “the commons” to also include “understanding knowledge as a commons” (Hess & Ostrom 2011). Open access activist Peter Suber showed how Open Access fits perfectly in such a theoretical background: “Creating an Intellectual Commons through Open Access” (Suber 2011).

Interviews with scientists showed that a change in attitude has already taken place. More and more scientists admit that they quickly change to another content related, but accessible article if they experience access problems. Also, Open Access seems to be a modern prolongation of a central traditional scientific habit for many scientists: make your work accessible to colleagues. This was done in former times with the help of offprints. Open access to an article may be seen as a modern solution for such scientific needs.

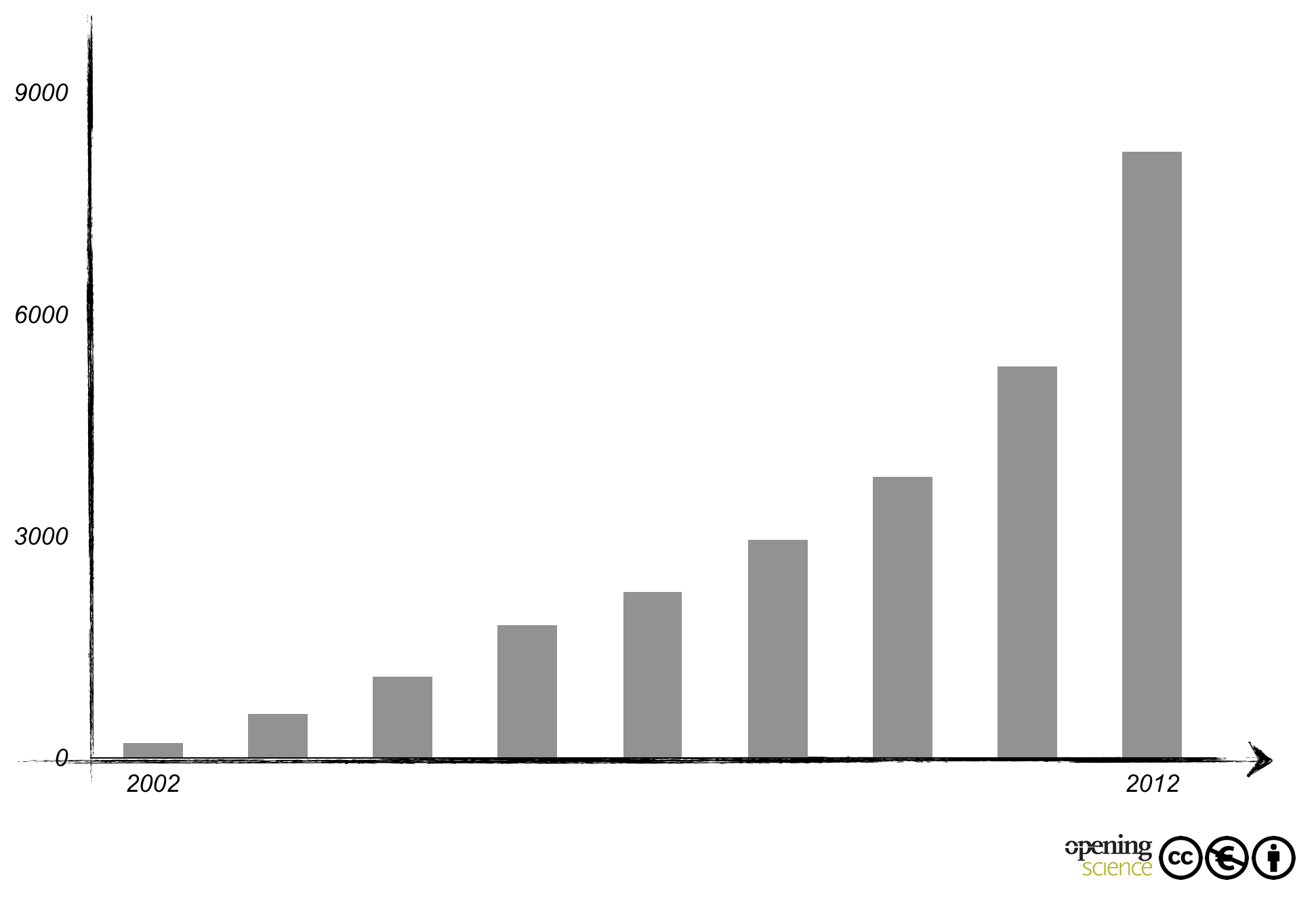

Some numbers show how broad the idea of open access is, how many already are using Open Access, and how quickly it is still growing. “Base”, a service built by the University Library Bielefeld, is harvesting the world of repositories (Green Open Access) and indexing their contents. It now contains over 35 million items, which compares to a total of about 1 million collected items in 2005.3 The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) gives an overview of Open Access Journals (Gold Open Access). In 2002, they counted 33 journals. Currently, the steadily increasing number has reached more than 8000 open access journals (Figure 2).

“Green” and “Gold” are the two well established and complimentary used roads to Open Access. Open Access depends upon these basic concepts, but, of course, a number of mixed concepts have also been established (for detailed information see Suber 2012).

A Closer Look at Green and Gold Open Access

Traditional journal subscription denies access to all those whose institution cannot afford to pay yearly subscription fees. In contrast, Gold Open Access describes a business model for journal publishing which gives free access to all potential readers and sees other models to cover expenses for a publication. Although there is a broad range of models, a majority of notable Open Access journals rely on publication fees, also known as article processing charges (ACP), which are often also incorrectly referred to as author fees. These sums are usually paid by the author’s institution. Especially in science, technology, and medicine, this follows the practice of paying for color images, too many pages, or other factors, which has been familiar since pre-Internet times in subscription-based journals. On the other hand, society journals in particular have opened access to their journal articles without charging authors. Others, like PNAS, give access after an embargo of half a year.

In the early times of Open Access an often heard argument against golden journals was the question of quality. Open Access journals differ only in terms of the publisher’s business model from subscription-based journals; they pass through the same peer review processes as the traditional journals and there are no differences regarding the quality of the published articles. Newly founded journals need some time to build a positive resonance in their research community. Today, Open Access journals are, of course, embedded within the high ranking journals in their fields. More and more get listed, e.g. in the Journal Citation Report of Thomson-Reuters (more than ten percent of all ranked titles).4 Laakso et al. (2011) give a comprehensive overview of the development using a distinction between “The pioneering years (1993–1999), the innovation years (2000–2004), and the consolidation years (2005–2009)”. For the future a more numerous migration from existing and valued subscription journals to the Gold model is desirable.

However, Open Access is not only possible for articles in journals with these respective business models. The Green Road of Open Access stresses the possibility of authors to deposit their articles, which are primarily published on publisher’s sites, additionally on another server. Usually an institutional or a subject-based repository is used for this purpose. “A complete version of the work and all supplemental materials, including a copy of the permission as stated above, in an appropriate standard electronic format is deposited (and thus published) in at least one online repository using suitable technical standards” (Berlin Declaration). An institutional repository is organized by an institution and contains the publications of its scientists. Opposed to the affiliation to an institution as a criterion for content, a subject-based repository comprises publications which belong to some specific fields of science. A famous example of a subject-based repository is ArXiv which already laid the grass roots for Open Access in the nineties. PubMedCentral is another example within the field of biomedical and life sciences research.

In principle, between 70 and 80% of scientific journals allow such a method of self-archiving. Generally there are some restrictions which have to be complied by the authors. In the majority of cases, depositing a version of the original article is not allowed, but rather a preprint or a version of the final draft. Depending on the journal, this can either be done immediately, or an embargo period between the publication of the original article and the self-archiving has to be considered. This period is usually between six (for STM journals) and twelve months (for social sciences and humanities journals). All journals which allow self-archiving are listed in the SHERPA/Romeo database which also lists the specific restrictions.

Meanwhile, many scientific institutions run an institutional repository to deposit green open access articles. Usually the library is responsible for this task. The deposit of their articles in such a repository has numerous advantages for the scientists.

One large benefit is made up of the support the repository operator offers its users. The scientists in question may ask for advice in all questions concerning the workflow of posting their publications. This includes, for example, when and in which form there are allowed to deposit a journal article. Digital preservation of the stored material is ensured as soon as explicit identification like persistent identifiers is provided. Furthermore, they make sure that all publications are tagged with precise and standardized metadata. Only in this way is cross-linking with other sources or other repositories possible, and, in turn, future features like semantic web functions will be possible. Correctly prepared data also enhances search engine exposure. In future, the linking between publications and the data which belongs to them, for example supplementary material or research data, will be relatively easy to establish on this level.

The content of an institutional repository is not limited to journal articles. By posting all of their publications, like reports, talks, conference proceedings, teaching materials, and so forth, into the repository, the scientists can present their work openly as a whole within the context of their research group and institution.‘’ If this open access repository is combined with an institutional research information system (CRIS), numerous benefits can emerge.’’Authors can re-use this content by linking to their openly accessible publications from social networks for scientists, their own homepage, etc. Through this linking, it is possible to connect the advantages of an institutional repository with the scientist’s personal needs. It can also be used as a helpful tool for the management of publications.

Scientists should demand such a database from their institutions if such a service is not yet offered. Not only the scientists in question, but also the whole institution benefit from a well-run institutional repository. A presentation of the research output of an institution in this way can constitute an important element for science marketing. For example, a Google search on articles shows the institutional homepage with the repository output, instead of a publisher’s homepage. It hence serves as a showcase of the research output of an institution (cf. Armbruster & Romery 2010). Therefore, it should also be in their interest to build such systems.

Institutional repositories mostly deal with final drafts. Subject-oriented repositories are based on specific traditions in certain scientific fields. Surely the most famous is ArXiv, founded in the early nineties for researchers in Theoretical Physics. Today it is a preprint archive for a broad range of scientific subjects. A recent Nature article states: “Population biologists turn to pre-publication server to gain wider readership and rapid review of results” (Callaway 2012).

PubMedCentral on the other hand, is a subject repository which, amongst others, hosts NIH-sponsored manuscripts, while RePEc (Research Papers in Economics) has successfully built a service based on the long tradition of publishing reports in economics. In future, both repository types should get better linked. If an article is deposited in one type, linkage to the other should become a standard.

Green or Gold: Which is the Better Way?

The recommendations of the British Working Group on Expanding Access to Published Research Findings, the Finch Report preferred Gold to Green. This triggered a discussion on what the best way to Open Access is (see, for example, Harnad 2012 or Suber 2012). Obviously, seen from a scientist’s point of view, both ways have the right to exist. Looking at the green road means publishing an article wherever one thinks it is the best for one’s career. At the same time, one makes use of the opportunity to give access to all relevant readers. Funders’ mandates will not be a problem, the green road is compliant. If self-archiving is supported by a well made institutional infrastructure, this way works quickly and easily. Additional costs are generated from infrastructural needs. In too many institutions there is still poor help for researchers; too often they are still left alone to self-archive. Hence, institutions should not only state policies, but actively support their scientists and strengthen infrastructural backing.

Meanwhile, the golden road is part of an axiomatic change of the publication landscape. It is a primary publication, which gives immediate access to an article in the context of its journal, including linkage to all additional services of a publisher. “… journals receive their revenues up front, so they can provide immediate access free of charge to the peer-reviewed, semantically enriched published article, with minimal restrictions on use and reuse. For authors, gold means that decisions on how and where to publish involve balancing cost and quality of service. That is how most markets operate, and ensures that competition on quality and price works effectively. It is also preferable to the current, non-transparent market for scholarly journals.”, as the secretary to the Finch committee puts it (Jubb 2012).

Naturally of course, again, the respective traditions of research fields matter. Björk et al. write “There is a clear pattern to the internal distribution between green and gold in the different disciplines studied. In all the life sciences, gold is the dominating OA access channel. The picture is reversed in the other disciplines where green dominated. The lowest overall OA share is in chemistry with 13% and the highest in earth sciences with 33%.” (Björk et al. 2010).

New Models

Of course, publishing has its costs and whatever way is followed, someone has to cover these. In the case of green repositories, infrastructure needs to be supported by institutions. Article processing charges for gold publishing are paid by funders or institutions. Most funders have already reacted and financing at least a part of open publishing fees has become a standard. Unfortunately, many institutions currently lack an appropriate workflow for this new challenge. Traditional journal subscription is generally paid for by libraries. In institutions it often is not clear to scientists, by whom and how these open access charges can be managed. Initiatives like the “Compact for Open-Access Publishing Equity” are paving the way to such workflows in order to make them a matter of course. The Study of Open Access Publishing (SOAP) gave evidence of this challenge: “Almost 40% [scientists] said that a lack of funding for publication fees was a deterrent …” (Vogel 2011). Institutional libraries must face this challenge and take on a new role. This new role is not too far from their traditional role: paying for access to information as a service for scientists. Björn Brembs even sees the future in a “library-based scholarly communication system for semantically linked literature and data” instead of the traditional processes dominated by publishers (Brembs 2012). SCOAP3 (Sponsoring Consortium for Open Access Publishing in Particle Physics) “is currently testing the transition of a whole community”, integrating scientific institutions, their libraries, and publishers.

Some publishers feature a hybrid model. They still back the traditional subscription model, but also offer an opportunity to buy out an individual article for Open Access. Seen from a scientist’s point of view this may be interesting, but usually the price level is high and only a few authors utilize this option. Seen from an institutional point of view, this is a problematic business model, as article fees and subscription fees are normally not yet combined. Therefore, institutions pay twice to a publisher (Björk 2012). Obviously such a hybrid is not a transition path to Gold.

Since traditional publishers have adopted the Open Access business model (e.g. Springer in 2010), we have definitely reached a situation in which Open Access has grown-up.

All stakeholders of the scholarly communication have to check carefully and adjust their roles in future, as new stakeholders will arise. They have been closely connected with each other for a long time. Open Access brought new functions and tasks for each stakeholder within the classical distribution; not all have already faced up to that challenge. For example, a lot of publishers are still locked up in thinking in print terms. In parallel, a common fear is that ACPs will go up and up when traditional publishers adopt the gold model and will become unaffordable. Charges differ within a broad range of some hundred Euros up to over 3000 Euros (Leptin 2012).

We now see a mixture of the roles mentioned. As an example, libraries can, in certain cases like grey literature, switch to a publisher’s role. On the other hand, “Nature” experimented with preprint publication, opening in 2007 “Nature precedings”, closing down the platform again in 2012. Due to Open Access, new publishing houses were set up. Some have quickly become respectable and successful, others may be under suspicion to be predatory (see Code of Conduct of the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association). Besides, new players are in the game and it is not yet decided as to where their role will lie. Publication management systems and scientific social networks are merging, often relying on Open Access full-texts.

But not only the players have to re-define their role within the scientific publications process; the format of scientific knowledge is also changing: “It no longer consists of only static papers that document a research insight. In the future, online research literature will, in an ideal world at least, be a seamless amalgam of papers linked to relevant data, stand-alone data and software, ‘grey literature’ (policy or application reports outside scientific journals) and tools for visualization, analysis, sharing, annotation and providing credit. … And ‘publishers’ will increasingly include organizations or individuals who are not established journal publishers, but who host and provide access and other added value to this online edifice. Some may be research funders, such as the National Institutes of Health in its hosting of various databases; some may be research institutions, such as the European Bioinformatics Institute. Others may be private companies, including suppliers of tools such as the reference manager Mendeley and Digital Science, sister company to Nature Publishing Group” (Nature 2012).

Books and Grey Literature

For a long time, scientific journals were in the center of Open Access discussions. Since e-books in scholarly publication are also emerging very quickly, we will soon see more developments in this field. Of course, business models are not one to one transferable from journals to monographs. Nevertheless, it already is clear that there is also a model for commercial publishers. Often an electronic version of a book is published Open Access and the publisher gets revenues by selling the printed version. In some fields, monographs mostly consist of a compilation of articles. In these cases, their handling could be comparable to journals. Maybe Springer’s move in August 2012 to introduce Open Access Books will be copied by other publishers. In the sciences it is familiar and a long standing tradition that an institution supports publishing a book by paying high contributions to publishers. It is just a matter of establishing a new culture to change the underlying standardized contracts in two points. Firstly, to retain rights for authors and institutions, secondly, to introduce some kind of Open Access, perhaps including an embargo.

So called “grey literature” has always played a role in scholarly communication and was mostly defined by its poor findability and dissemination. Usually, grey literature was published by scientific institutions in print with a low circulation rate. But if the content is trusted, reviewed, and is published Open Access by a reputable institution in its own electronic publishing infrastructure, grey literature is up for playing a new and sustainable role in a future publication landscape. Some even see this as a nucleus for a rearrangement of roles (see Huffine 2010). Hereby, libraries could be one of the key players. Important for an Open Access future of grey literature is a thoroughly-built infrastructure which guarantees quality, persistence, and citability. New and emerging ways of scholarly communication can be included in such a structure.

The important role of research data for an Open Science is discussed elsewhere in this book (see Pampel & Dallmeier-Tiessen in this volume). Scholarly text publication and data publication cannot be separated in the future. On the side of Open Access for texts, a close connection to related data needs to become part of scholarly common sense. Text and data should be seen as an integral unit which represents the record of science of a researcher. As Brembs puts it: “Why isn’t there a ‘World Library of Science’ which contains all the scientific literature and primary data?” (Brembs 2011). Talking about data mining will always have both parts in mind: text and related research data.

Impact of Open Access on Publishing

In addition to establishing new business models, Open Access has featured and accelerated elementary changes in scientific publishing. The general impact of Open Access upon the development of scholarly publishing is tremendous.

Peer review is one issue. Already ten years ago, for example, Copernicus Publications, the largest Open Access publisher in geosciences, combined open access publishing with a concept of open interactive peer review (Pöschl 2004).

The rise of PLOS ONE, an Open Access mega journal promising quick peer review and publication and accepting articles from all fields, has changed the scene. PLOS, which is now the largest scientific journal worldwide with around 14.000 articles per year, has been followed by a chain of new established journals from other publishers copying the model. Just to name a few new Open Access journals, and having a look at the publishers in the background, this following list shows how important mega journals have become: Springer Plus, BMJ open, Cell reports, Nature communications, Nature Scientific Reports, and Sage Open.

Giving away all rights to the publisher when signing an author’s contract has been one of the strongest points of criticism for years. Discussions on how authors can retain copyright brought Creative Commons licenses into the focus. Today, Creative Commons licenses like CC-BY or CC-BY-SA have become a de facto standard in Open Access publishing (see as an example Wiley’s recent move to CC-by).5 “Re-use” is the catchword for the perspective which has been opened by introducing such licenses.

Benefits

Open Access publications proved to have citation advantages (Gargouri et al. 2010) resulting from open accessibility of scholarly results formerly only available in closed access. It guarantees faster communication and discussion of scientific results. Therefore, it perfectly assists in fulfilling the most basic scholarly need: communication. Open Access also promotes transparency and insight for the public into scientific outcomes (Voronin et al. 2011). The outreach of scientific work is stimulated.

Tools for a new and comprehensive findability and intensive data mining to openly accessible texts will certainly be available. This will make interdisciplinary work easier and productive. Reuse, due to open licenses, the “possibility to translate, combine, analyze, adapt, and preserve the scientific material” is easier and will lead to new outcomes (Carroll 2011).

The statement “In the online era, researchers’ own ‘mandate’ will no longer just be ‘publish-or-perish’ but ‘self-archive to flourish’” (Gargouri et al. 2010) can be extended to “researchers’ own ‘mandate’ will no longer just be ‘publish-or-perish’ but give open access to flourish”.

References

Armbruster, C. & Romary, L., 2010. Comparing Repository Types - Challenges and barriers for subject-based repositories, research repositories, national repository systems and institutional repositories in serving scholarly communication. International Journal of Digital Library Systems, 1(4), pp.61–73.

Brembs, B., 2011. A Proposal for the Library of the Future. björn.brembs.blog. Available at: http://bjoern.brembs.net.

Brembs, B., 2012. Libraries Are Better Than Corporate Publishers Because… björn.brembs.blog. Available at: http://bjoern.brembs.net.

Callaway, E., 2012. Geneticists eye the potential of arXiv. Nature, 488(7409), pp.19–19. doi:10.1038/488019a.

Harnad, S., 2012. Open access: A green light for archiving. Nature, 487(7407), pp.302–302. doi:10.1038/487302b.

Hess, C. & Ostrom, E., 2011. Understanding knowledge as a commons: from theory to practice, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Huffine, R., 2010. Value of Grey Literature to Scholarly Research in the Digital Age. Available at: http://cdn.elsevier.com/assets/pdf_file/0014/110543/2010RichardHuffine.pdf.

Jubb, M., 2012. Open access: Let’s go for gold. Nature, 487(7407), pp.302–302. doi:10.1038/487302a.

Nature, 2012. Access all areas. Nature, 481(7382), pp.409–409. doi:10.1038/481409a.

Pöschl, U., 2004. Interactive journal concept for improved scientific publishing and quality assurance. Learned Publishing, 17(2), pp.105–113. doi:10.1087/095315104322958481.

Suber, P., 2011. Creating an Intellectual Commons through Open Access. In C. Hess & E. Ostrom, eds. Understanding Knowledge As A Commons. From Theory to Practice. Massachusetts, USA: MIT Press, pp. 171–208.

Suber, P. ed., 2012. What is Open Access? In Open Access. Massachusetts, USA: MIT Press, pp. 1–27.

Vogel, G., 2011. Open Access Gains Support; Fees and Journal Quality Deter Submissions. Science, 331(6015), pp.273–273. doi:10.1126/science.331.6015.273-a.

Voronin, Y., Myrzahmetov, A. & Bernstein, A., 2011. Access to Scientific Publications: The Scientist’s Perspective K. T. Jeang, ed. PLoS ONE, 6(11), p.e27868. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027868.

Willetts, D., 2012. Open, free access to academic research? This will be a seismic shift. theguardian. Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/may/01/open-free-access-academic-research?CMP<nowiki\=/nowikitwt\_gu.

For interested readers, further information and interesting discourses are provided here:

Eckman, C.D. & Weil, B.T., 2010. Institutional Open Access Funds: Now Is the Time. PLoS Biology, 8(5), p.e1000375.

Evans, J.A. & Reimer, J., 2009. Open Access and Global Participation in Science. Science, 323(5917), pp.1025–1025.

Grant, B., 2012. Whither Science Publishing? TheScientist. Available at: http://www.the-scientist.com.

Hawkes, N., 2012. Funding agencies are standing in way of open access to research results, publishers say. BMJ, 344(jun11 1), pp.e4062–e4062.

Nature, 2010. Open sesame. Nature, 464(7290), pp.813–813.

Nature, 2012. Openness costs. Nature, 486(7404), pp.439–439.

Noorden, van, R., 2012. “Journal Offers Flat Fee for ‘All You Can Publish’.” Nature 486, no. 166.

Science, 2012. The Cost of Open Access. Science, 336(6086), pp.1231–1231.

Shotton, D., 2009. Semantic publishing: the coming revolution in scientific journal publishing. Learned Publishing, 22(2), pp.85–94.

Whitfield, J., 2011. Open access comes of age. Nature, 474(7352), pp.428–428.

Björk, B.-C., 2012. The hybrid model for open access publication of scholarly articles: A failed experiment? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(8), pp.1496–1504. doi:10.1002/asi.22709.

Björk, B.-C. et al., 2010. Open access to the scientific journal literature: Situation 2009. PLoS ONE, 5(6), p.e11273. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011273.

Boulton, G. & et al., 2012. Science as an open enterprise, London, UK: The Royal Society. Available at: http://royalsociety.org/policy/projects/science-public-enterprise/report/.

Carroll, M.W., 2011. Why full open access matters. PLoS Biology, 9(11), p.e1001210. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001210.

Gargouri, Y. et al., 2010. Self-selected or mandated, open access increases citation impact for higher quality research. PLoS ONE, 5(10), p.e13636. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013636.

Laakso, M. et al., 2011. The development of open access journal publishing from 1993 to 2009. PLoS ONE, 6(6), p.e20961. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020961.

Leptin, M., 2012. Open access–Pass the buck. Science, 335(6074), pp.1279–1279. doi:10.1126/science.1220395.

European Commission: http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf\_06/era-communication-towards-better-access-to-scientific-information\_en.pdf↩

Faculty Advisory Council Memorandum on Journal Pricing: http://isites.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=k77982&tabgroupid=icb.tabgroup143448↩

BASE Statistics: http://www.base-search.net/about/en/about_statistics.php?menu<nowiki\=2/nowiki↩

Thomson Reuters Intellectual Property & Science: http://science.thomsonreuters.com/cgi-bin/linksj/opensearch.cgi?↩

Wiley Moves Towards Broader Open Access Licence: http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/PressRelease/pressReleaseId-104537.html↩

Next chapter: Novel Scholarly Journal Concepts

Peter Binfield