Abstract

As high as the potential of Web 2.0 might be, the European academia, compared to that of the US, mostly reacts hesitantly at best to these new opportunities. Interestingly enough this scepticism applies even more to science communication than to scientific practice itself. The author shows that the supposed technological challenge is actually a cultural one. Thus possible solutions do not primarily lie in the tools or in the strategies used to apply them, but in the adaptation of the systemic frameworks of knowledge-creation and dissemination as we have practised them for decades, if not centuries. Permeating an ‘Open Science Communication’ (OSC) under closed paradigms can only succeed if foremost the embedding frameworks are adapted. This will include new forms of impact measurement, recognition, and qualification, and not only obvious solutions from the archaic toolbox of enlightenment and dissemination. The author also illustrates the causes, effects, and solutions for this cultural change with empirical data.

Change happens by listening and then starting a dialogue with the people who are doing something you don’t believe is right. Jane Goodall, British ethologist and a devoted science communicator

The swan song of what was meant to be an era of “Public Understanding of Science and Humanities” (PUSH) rings rather dissonantly today, given the wailing chorus of disorientation, if not existential fear, intoned by science communicators across Europe. Almost 30 years after the game-changing Bodmer report (Royal Society 1985), another paradigmatic shift is taking place, probably even more radical than any of the transitions during the previous four eras (Trench & Bucchi 2010; Gerber 2012). This fifth stage of science communication is being predominantly driven by interactive online media. Let us examine this from the same perspectives which the very definition of “science communication” as an umbrella-term also comprises of: 1. the communication about science, and 2. the communication by scientists and their institutionalised PR with different publics.

Communication about Science

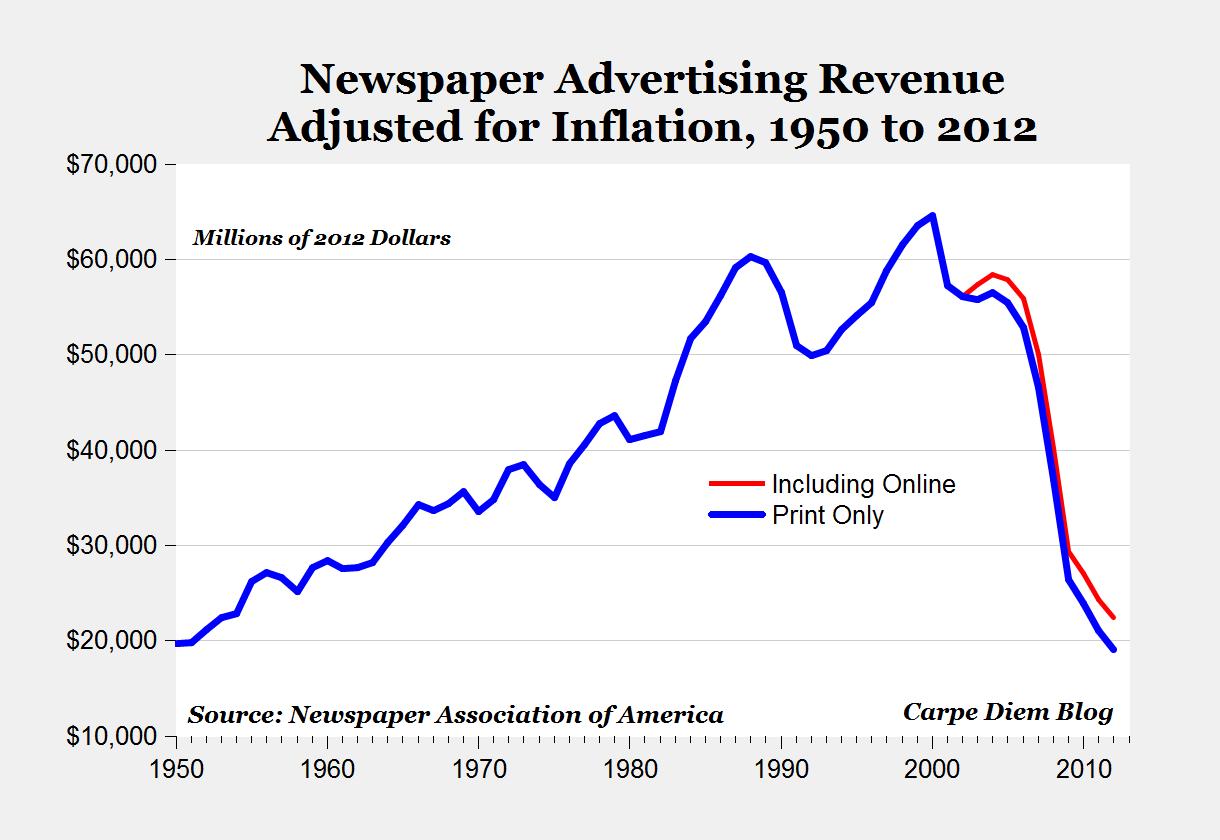

Journalists are witnessing a widespread disintegration of mass media outlets and their underlying business models. In terms of circulation and advertising revenue, this demise may not be as abrupt as in the U.S. (see Figure 1), but is surely just as devastating for popular science publishers in Europe, and consequently their staff and freelancers in the long run (Gerber 2011). Geoff Brumfiel (2009) was among the first scholars to make the scientific community aware of the extent of the science journalism crisis, quoting blatant analyses by experienced editors, such as Robert Lee Hotz from The Wall Street Journal: “Independent science coverage is not just endangered, it’s dying” (p. 275). Afflicted by low salaries and even lower royalties from a decreasing number of potential outlets, science journalism is additionally (or maybe consequently) suffering from a continuous decrease in credibility.

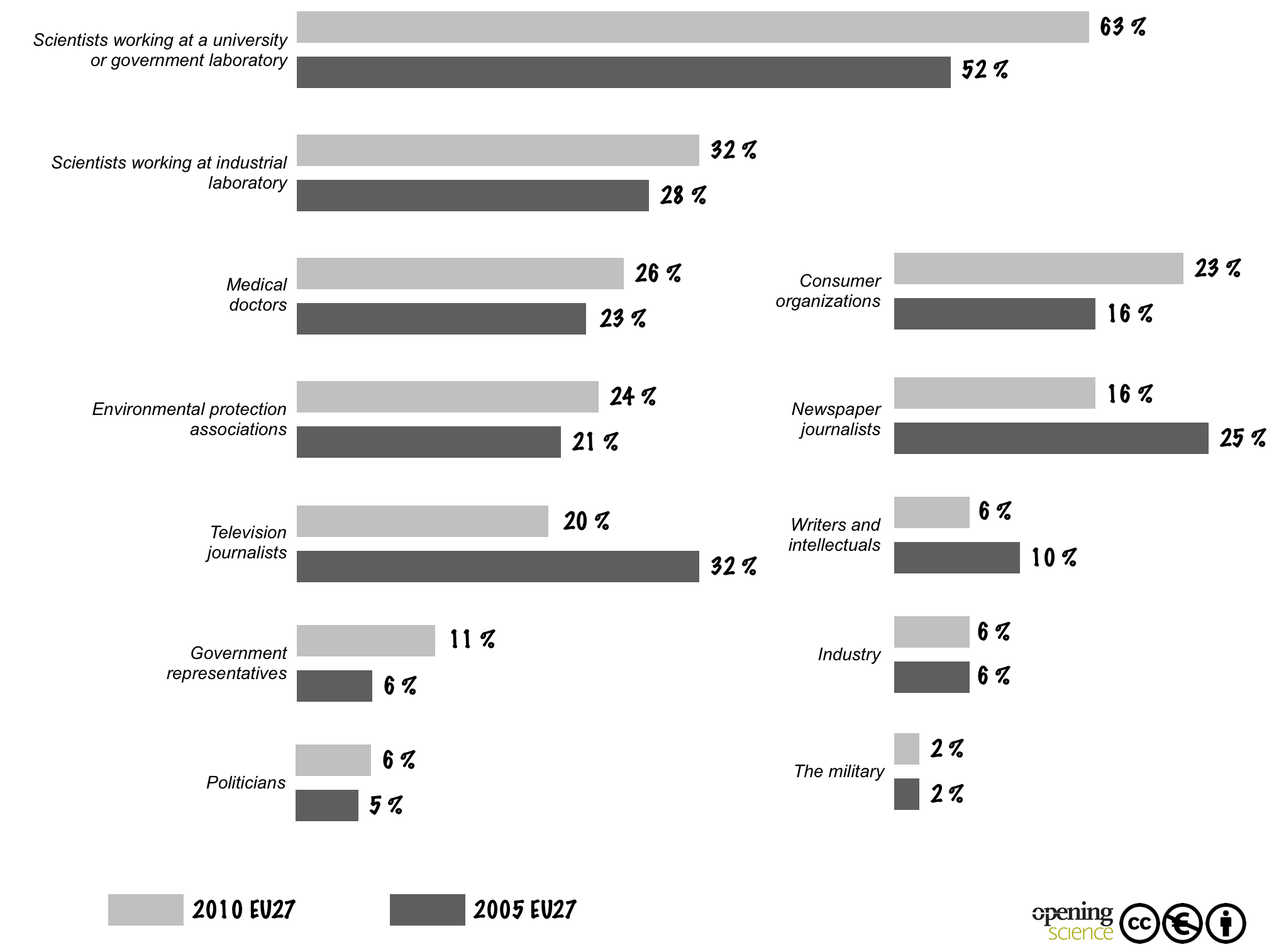

Questioned about who is most appropriate to explain the impact of science upon society, only 16–20 % of Europeans nowadays name journalists—a further decrease from 25–32 % five years before (see Figure 2). In fact, a majority expects the scientists themselves to deliver their messages directly: 63 %, increasing from 52 % five years earlier (European Commission 2010). Unfortunately, it has not yet been investigated properly as to what extent this credibility also (or particularly) extends over the science blogosphere and other online platforms, or whether interactive online media have even been catalysts, and not just enabling technologies, in this development.

Every discourse or effort to reinvent journalism regarding media economics (e.g. crowdfunding), investigation methods (e.g. data-driven journalism in the deep web), formats (e.g. slide casts), and distribution (e.g. content curation) almost inevitably seems to circle around interactive online media. Obviously the web is not only seen as the main cause of the crisis, but also as the main opportunity for innovations to solve it.

On the other hand, one could also argue that due to an increasing number of popular science formats on television, science journalism now reaches a much wider audience as compared to print publications which have always merely catered to a small fraction of society. Especially on TV, however, we as communication scholars should be wary of the distorted image of science reflected by conventional mass media. Coverage and content are mostly limited to either the explanation of phenomena in everyday life (“Why can’t I whip cream with a washing machine?”) or supposed success stories (“Scientists have finally found a cure for Cooties”). Thereby journalism neither succeeds in depicting the ‘big science picture’ of policy, ethics, and economics holistically, nor the real complexity of a knowledge-creation process authentically, which is everything but linear, being a process in which knowledge is permanently being contradicted or falsified, and is therefore never final.

However, the notion of what the essence of science really is could perfectly well be vulgarised through web technologies, in the sense of making the different steps within this process of knowledge-creation transparent, for instance by means of a continuous blog or other messaging or sharing platforms. Yet there are still only very few examples for such formats (see below), and they are particularly sparse in journalism.

The tendency to reduce science to supposed success stories is certainly also a result of its mediatisation, i.e. science and science policies reacting and adapting to the mass media logic by which it is increasingly being shaped and framed (Krotz 2007; Fuller 2010; Weingart 2005). This brings us to the second dimension of science communication.

Communication by Scientists and the Institutionalised PR

Self-critical scholars as well as practitioners of science communication wonder how far we have effectively come since 1985, when the Royal Society envisioned a public which would understand “more of the scope and the limitations, the findings and the methods of science”. Even then the “most urgent message” went to the scientists themselves: “Learn to communicate with the public, […] and consider it your duty” (The Royal Society 1985, p. 24).

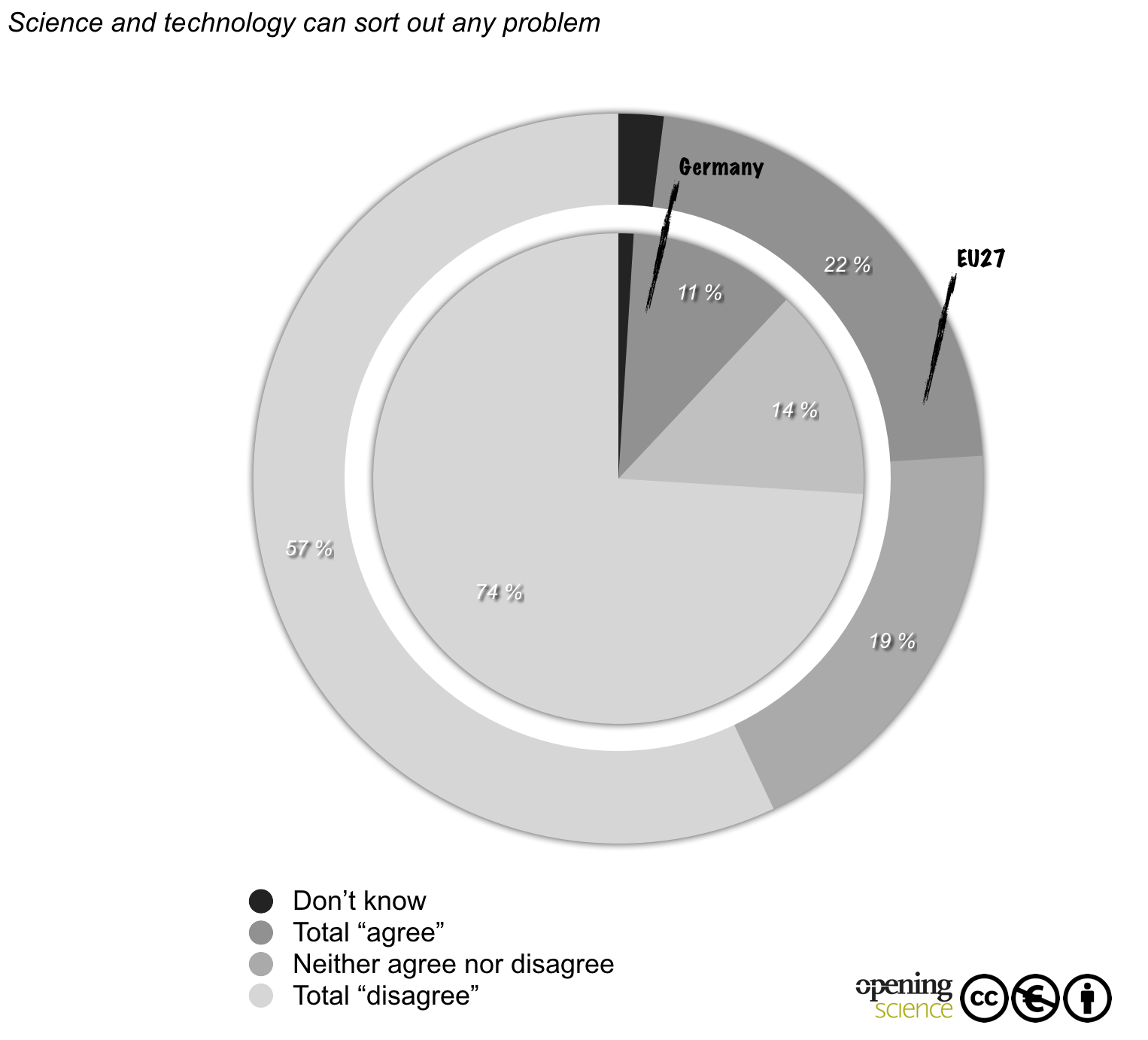

Almost 30 years later the resources for institutionalised science PR and marketing have multiplied remarkably. Compared to the early 90s when professional communicators were rare exceptions, there is hardly a single university or institute left today without a communication department. Larger institutions employ up to 70 full-time communicators in the meantime. Yet less than one out of ten citizens in Europe actually show any interest whatsoever in science centres, public lectures, or science fairs (European Commission 2010, see Figure 3)—albeit with a blanket coverage across the continent. Such obvious contrasts between the supply and demand of certain formats make science an easy prey for critics arguing that its communication is inherently elitist. At least the often misinterpreted decrease in naïve trust in science—66 % in 2010 compared to 78 % in 2005 (European Commission 2010)—is an encouraging sign of an increasingly critical public (Bauer 2009).

PR professionals have been ‘PUSH-trained’, so to speak, to focus on the dissemination of research results, ideally in the form of a well-told success story, as described above, and thereby significantly contribute to the distorted media image of scientific reality. Unfortunately just now that science, at least on an institutional level, seems to have come to terms with the mechanisms of mass media; PR and marketing are being shattered by a seismic shift towards a horizontalisation of communication better known as social media. Particularly the new media-savvy student generations have an entirely different understanding of how the relevant information should ‘find them’. Even most communication scholars are still amazed of the pace of this transition. In countries like Germany, for instance, the Internet overtook television two years ago in terms of activated and structured demand for information, i.e. the medium of choice to look for quality information—an increase from 13 % in 2000 to 59 % in 2011 (IfD Allensbach 2011).

Unanimously most studies show, however, that science has as of yet largely avoided adapting both its communication efforts and its own media usage to the above mentioned changes in the information behaviour of laypeople (Procter et al. 2010; Bader et al. 2012; Allgaier et al. 2013). In a web technology use and needs analysis Gerber (2012; 2013) showed that the use of even the most common online tools is still a niche phenomenon in the scientific community. Furthermore, the few well-known tools were also the ones to be the most categorically rejected, e.g. Twitter by 80.5 % of the respondents.

Yet the diffusion of Web 2.0 tools in academia is only partly a question of technology acceptance. For instance, online communication is still not taken into account in most cases of evaluation or allocation of research funding. Most experts in a Delphi study on science communication (Gerber 2011) therefore demand a critical discourse about possible incentives for scientists. If online outreach, however, became a relevant criterion for academic careers, we would also have to find more empirically sound ways to measure, compare, or even standardise and audit the impact of such an outreach. Approaches like ‘Altmetrics’ are promising but still in a conceptual phase. At least for another few years we will therefore have to deal with a widening gap between the masses of scientists communicating “ordinarily”, on the one hand, and the very few cutting edge researchers and (mostly large and renowned) institutions experimenting extensively with the new opportunities, on the other. Thus the threat of increasing the already existing imbalances between scientific disciplines is just as evident as the opportunities for increasing transparency, flattening hierarchies, or even digitally democratizing the system itself, as sometimes hyperventilated by Open Science evangelists.

We must not forget that technologies only set the framework, whereas the real challenges and solutions for an ‘Open Science Communication’ are deeply rooted in scientific culture and the system of knowledge creation itself (Gerber 2012). Much will, therefore, depend upon the willingness of policy makers to actively steer the system in a certain direction. Yet they also have to reconsider whether they thereby risk fostering (even unintentionally) the above mentioned distortion of scientific practice. The ultimate challenge lies in balancing incentives and regulations, on the one hand, with the inevitable effect of a further mediatisation of science, on the other, since both remain two sides of the same coin.

Public relations and science marketing professionals will keep struggling with the increasing ‘loss of control’ as long as they hang on to their traditional paradigm of dissemination. An increasing number of social media policies in academia shows that the institutions have realised the challenges that they are facing in terms of governance. By accepting ‘deinstitutionalisation’ and involving individual scientists as authentic and highly credible ambassadors (see above), PR can make the most essential step away from the old paradigm to the new understanding of Open Science Communication (OSC).

The common ground for both above mentioned trends—the ‘deprofessionalisation’ of science journalism and the ‘deinstitutionalisation’ of science communication at large—is the remarkable amount of laypersons finding their voices online and the self-conception of civil society organisations demanding to be involved in the science communication process. As much as this inevitably shatters the economic base of science journalism and as much as it may force the science establishment to reinvent its communication practice, we should be grateful for the degree of communication from ‘scientific citizens’. Thereby the challenge lies less in permitting (or even embracing) bottom-up movements as such, but rather more in resisting the use of public dialogue as a means to an end. While valorising ‘citizen science’ as an overdue ‘co-production’ of authoritative social knowledge, Fuller warns us not to treat broadcasts of consensus conferences, citizen juries, etc. simply as ‘’“better or worse amplifiers for the previously repressed forms of ‘local knowledge’ represented by the citizens who are now allowed to share the spotlight with the scientists and policy makers.”’’(2010, p. 292)

The questionable success of most of these public engagement campaigns has increasingly been challenged recently. Grassroots initiatives like ‘Wissenschaftsdebatte’ or ‘Forschungswende’ in Germany criticise openly the fact that pseudo-engagement has merely served as a fig leaf excuse for the legitimisation of research agendas which are still being built top-down. Instead it will be necessary to supplement the dragged-in rituals of ‘end of pipe’ dissemination with a fresh paradigm of ‘start of pipe’ deliberation.

Undoubtedly such initiatives cater to the transparency and true public engagement pursued by the ideal of Open Science. Thus within the ‘big picture’ we should embrace the opportunities of the OSC era, and in particular the interactive online technologies driving it.

Outlook

Driven by interactive online media, OIC has the potential to exceed the outdated view of communication as a ‘packaging industry’. In the next few years we can expect a second wave of professionalisation in science PR and marketing, e.g. through specialised social media training. The performance of communication professionals (and probably also the performance of scientists) will increasingly be measured by whether they succeed in truly engaging a much wider spectrum of society or not. New cultures of communication may foster a scientific citizenship but will also raise new questions regarding imbalances and distortion within the scientific system, and thus the challenge to measure communication impact properly, and even normalise and standardise these new measurements.

References

Allgaier, J., 2013. Journalism and Social Media as Means of Observing the Contexts of Science. BioScience, 63(4), pp.284–287.

Bader, A., Fritz, G. & Gloning, T., 2012. Digitale Wissenschaftskommunikation 2010-2011 Eine Online-Befragung, Giessen: Giessener Elektronische Bibliothek. Available at: http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2012/8539/index.html.

Bauer, M.W., 2009. The Evolution of Public Understanding of Science–Discourse and Comparative Evidence. Science Technology & Society, 14(2), pp.221–240. doi:10.1177/097172180901400202.

Brumfiel, G., 2009. Science journalism: Supplanting the old media? Nature, 458(7236), pp.274–277. doi:10.1038/458274a.

Dernbach, B. & Schreiber, P., 2010. Wissenschaft evaluiert.

European Comission, DG Research / DG Communication, 2010. Special Eurobarometer, Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_340_en.pdf.

Fuller, S., 2010. The mediatisation of science. BioSocieties, 5(2), pp.288–290. doi:10.1057/biosoc.2010.11.

Gerber, A., 2011a. Online Trends from the First German Trend Study on Science Communication. In Tokar, ed. Science and the Internet. Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University Press, pp. 13–18. Available at: http://bit.ly/SMS_COSCI12.

Gerber, A., 2013. Open Science without Scientists? Findings from the Social Media in Science study. Available at: http://bit.ly/SMS_EISRI.

Gerber, A., 2011b. Trendstudie Wissenschaftskommunikation - Vorhang auf für Phase 5. Chancen, Risiken und Forderungen für die nächste Entwicklungsstufe der Wissenschaftskommunikation, Berlin: Innokomm Forschungszentrum. Available at: http://stifterverband.de/wk-trends.

IfD Allensbach, 2011. Markt- und Werbeträger-Analyse (AWA).

Krotz, F., 2007. Mediatisierung: Fallstudien zum Wandel von Kommunikation 1. Aufl., Wiesbaden: VS, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Procter, R., Williams, R. & Stewart, J., 2010. If you build it, will they come? How researchers perceive and use web 2.0, Research Information Network. Available at: http://www.rin.ac.uk/our-work/ communicating-and-disseminating-research/ use-and-relevance-web20-researchers.

The Royal Society, 1985. The Public Understanding of Science, Available at: http://royalsociety.org/policy/publications/1985/public-understanding-science.

Trench, B. & Bucchi, M., Science communication, an emerging discipline. Journal of Science Communication JCOM, 9(3). Available at: http://jcom.sissa.it/archive/09/03.

Weingart, P., 2001. Die Stunde der Wahrheit? Zum Verhältnis der Wissenschaft zu Politik, Wirtschaft und Medien in der Wissensgesellschaft 1. Aufl., Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft.

Next chapter: Open Science and the Three Cultures: Expanding Open Science to All Domains of Knowledge Creation

Michelle Sidler